At the beginning of the 21st century, the functions of State borders have changed. Borders do not just contain but also overflow spaces, districts and jurisdictions. Borders are losing their linear aspects and are becoming more mobile and more diffuse in order to adapt to globalisation. Actors managing border control have also substantially multiplied. In addition to states, new stakeholders such as agencies, corporations, and NGOs have emerged as actors of border management. The ways in which people’s mobility is controlled are more and more diversified and differentiated. People have to pass through multiple networks and identification devices. All these mutations have to be analyzed in detail, using a wide range of modes of expression and critical tools.

Border Changes in the 21th Century

The transformation of borders is intimately connected to the ways globalization has altered productive chains, communication and defense systems, work and culture. Neoliberalism has promoted national reforms that include fiscal austerity, free trade and labor flexibility, while promoting global agreements on taxes, banking and accounting standards. Freedom of mobility has been conceived through an economic perspective. At the same time, there are new strategies which aim at containing migratory pressures through the selective filtering of human flows.

From flow control to risk management

These transformations have resulted in a contradiction between economic practices that increase unequal global development and the need to implement sustainable and fair global development. There is also a geopolitical contradiction between national governments’ policies, which are limited by their sovereignty, and the need to regulate transnational processes through global governance frameworks. To address these contradictions, national governments have assigned state borders the function to guarantee people’s security in a world characterized by transnational mobility of people, capital, goods and ideas. In other words, borders are supposed to allow a high level of mobility while protecting against social, economic, political, and public health risks the mobility of people generate.

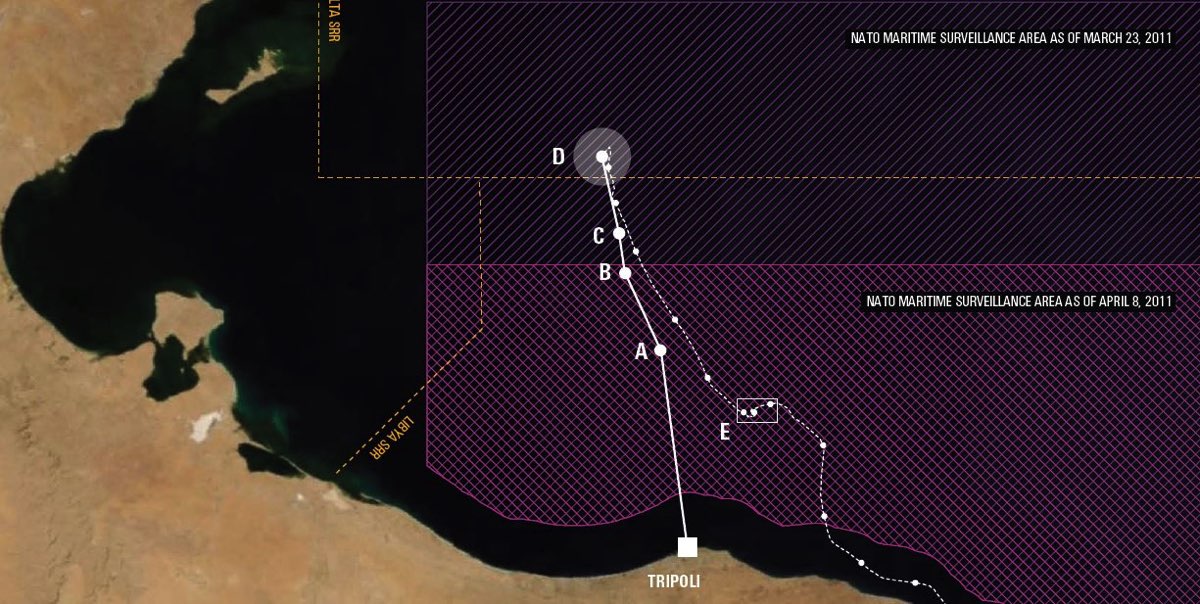

The role of borders as effective means of security has declined because of the difficulty to distinguish between internal and external origin of migrations, terrorism, economic and financial flows, software piracy and pollution. The lines between domestic and external security have become blurred to such extent that these domains are difficult to separate clearly. In this context, border control is conceived and implemented in a selective and individualized manner. The purpose of such control is not just to secure the national group in order to guarantee citizens’ well-being. Instead, the aim of border control is also to securitize individuals themselves in order to perpetuate the political existence of a national society. Seen in terms of risks, human, commercial and information flows are becoming the targets of surveillance. Border control has become a form of risk management. Because these movements overflow the national space and cannot be circumscribed by it, securitization strategies are now conceived on a global scale.

The objective of border securitization is less to fully close these flows than to improve the mechanisms to filter them. Borders are functioning as firewalls; they aim to allow legitimate traffic and contain unwanted people perceived as both risks and threats. Borders could be very porous to capital, but not to workers with low levels of formal education. The implementation of this new logic of control has led to an unprecedented process of integration of surveillance systems, such as borderland devices, biometry, numeric and satellite networks, RFID, drones, robots, radars, CO2 detectors and all other objects used to detect, identify and follow the movement of human bodies. This process has gained popularity based on the notion that technological automation will improve border control by reducing costs and human error.

Mutations of borders and shifting forms of mobility

Keeping flows under surveillance today means that border controls managed by police, custom services and private companies get redeployed inside the national territory as well as projected inside other States’ territories. Customs may operate in foreign ports and airports. Visa checks are carried out in the country of migrants’ origin, not only in embassies but also in private offices. Simultaneously, check points are multiplied in order to track people and providers of goods who have managed to circumvent surveillance systems. Lastly, in order to exclude certain categories of flows, special zones such as detention centres, staging areas in airports, or free zones have been created on uncertain juridical basis. Such increasingly selective control implies a diversification of circulatory regimes: regimes regarding the circulation of goods are increasingly constituted by WTO agreements on tariffs and trade, whereas the circulation regimes affecting human flows get managed through more or less coercive migratory policies. Border crossing chances are determined by a complex set of factors such as professional status, gender, natioanl origins, ethno-religious stereotypes, economic and linguistic capacities, affiliations, etc. In the post 9/11 context, new operational dilemmas have emerged due to contradictions between the constraints of securitization imposed by efforts to prevent terorrism and the efforts required to safeguard the fluidity of global trade.

The main outcome is the generalization of negociated mobility based on contingent arbitration: creating the conditions for fluidity and interconnections implies increasingly sophisticated overriding clauses. Major TNCs, for instance, bargain both accesses and tariffs. In this context, flagrant gaps between hyper-connected spaces or people and closed ones have emerged. The needs of people who are deprived of rights to circulate are cared for by an expanding humanitarian regime which goes further than basical asylum rights. NGOs take charge of « unwelcome » groups of migrants considered as vulnerable. Depending on how well they fulfill the ‘true victim’ stereotype, in which the presentation of a suffering body becomes key to arouse compassion and solidarity, migrants are granted fundamental rights. However, since ever more restrictive policies frame global migrations, access to asylum and welfare rights has drawn a humanitarian boundary line throughout the world.

The sophistication of entrance regulations leads to an individualization of controls, particularly on the basis of biometric data. People who wish to bypass the biometric control systems are obliged to modify their physical aspect, notably by achieving mutilation and erasure of fingerprints. Borders are now likely to be embedded in the person. Border management is embodied as it detaches from the territory. This means individualizing controls and biometric processing of borders.

Trespassing and diverting the rules of the game

These changes are all the more complex as they involve multiple actors. The companies and agencies who are mandated by national states to manage border surveillance have formed clusters of firms. The latter make money out of services that manage the mobility of humans, goods, and capitals. Some specialise in assisting procurement of visas or fast track work permits. Others, like consulting groups, optimize the means towards accelerated transborder freight. These groups build databases and provide global benchmarking for harbour logistics. As a result, control devices are set up to improve the power to control flows.

More informally, a high number of actors intercede in favour of modulated and moderated filtering, so that borders become more porous. Migratory traffic provide good examples of such arrangements. People smugglers have organized and have gained key positions in the system, as they can ease or obstruct entrance according to their own interests. They have become unofficial ‘regulation authorities’. Formal authorities cannot put an end to their networking and prefer to enlist them in fighting other forms of criminality. Thus, they incorporate informal networks to their own mechanisms of regulation and control.

Why an antiAtlas?

Atlases as map collections have instructed populations and delighted book lovers for centuries. Atlases are edifying objects. They provide a scientific representation of territorial divisions and a unifying glance at the world as a whole. Spatial sciences (topology, geometry, geography) have shown constant concern for sharp graphs and various scales. The history of border drawing consists of comings and goings between static and formal outlines and the fluidity of social experience. The instability of international relations has been benefic many geographers. Maps have always been political objects par excellence. The process through which border lines have stabilized is directly related to their mutual recognition in treaties. Making an atlas of borders means to experiment stability or to give the illusion of it. Setting the world in (right) order through maps is both a social and political process. So, why conceiving an antiatlas of borders ? Is it simply to create disorder?

A dynamic and critical approach

Our project may deceive both active partisans of order as well as internal enemies and partisans of disorder who look for innovative insights. Our project aims at a collective exploration. Talking about an anti-Atlas of borders first means that systematic graphic visualization of borders is not the most acceptable and desirable way of understanding borders. We do not contest the usefulness of maps as scientific tools, but the very idea that systematic compiling enlivened by comments may provide adequate knowledge of borders. Formal institutions are often in favour of geopolitical catalogues, insofar as this provides a synthetic vision of social and political relations. Such a titanic rendering of the world is less desirable to us than multiple investigations of complexity. Borders, beyond their topology, address ontological, morphological, sociological, anthropoligical and psychological issues – that is to say we shoud pay attention at the same time to their location, their mode of existence, their forms and shapes, their existing as social and mental facts, etc. Postulating a territorial order is less interesting today than assessing how far borders are made of physical inertia, to what extent they are socially constructed – and from which mobilizations and demobilizations – how they materialize and dematerialize contextually, how we encounter them as evolving devices, how they function as launchpads for deterrioralized control and surveillance, how they work mechanically, electronically, biologically, how they condition exchanges, produce formal and informal rules, and finally more or less random outputs of what is legitime and what is not. What is at stake is thus to understand the border as a perpetually changing process rather than as a simple place. Atlases produce a static and stable synthesis while an antiatlas produces a dynamic and critical analysis.

From scientific exploration to artistic experimentation

Initially conceived as an exploratory research project, the antiAtlas of borders has become a performance in the artistic meaning of the word. The fact that researchers, professionals of border control, and artists have met each other for ten seminars between 2011 and 2013 has of course allowed them to enrich their own approach. In addition, this has also led to uncommon transdisciplinary experiences through which original works have reffered to borders as they are lived: this has been the case when producing video games and films on the basis of anthropoligical observations, when managing participative cartography, etc. Moreover, artistic works have provided many explorations and experiences of our ambivalent relation to borders – one one side, what they make of us, of our identity, of our intimacy, of our body, etc.; on the other side, what do we make of them, how we give them material and immaterial visibility or invisibility, how we play with them, either for freeing of them, or for surveying and denouncing our contemporaries. Tactic media as diversions of surveillance are spectacular manifestations of such an ambivalence. These pieces help us to keep some distance with the domination/resistance alternative. They show that the relations between the rationality of control initiatives and the practices that evade them are perpetually replayed.

Favouring a dialogue between art, science, and practice, does not mean promoting a new ‘doxa’ for border studies. We simply assume that transdisciplinarity generates cognitive gains made of quotations, transfers and exemplification. Any discipline at any time may function as a vehicle for another one. None of each specific knowledge is confronted to the collapse of its proper logic, but committed in new experiments, with all the limits and benefits this may induce. This is the way the antiAtlas challenges our routines by pushing everyone for experimentation and taking completely different backgrounds into account.

From reality to virtuality

Approaching borders in the 21st Century supposes to perceive the transformations of spaces, both from space constitutencies and common experiences. This makes them a major element of our way to express how the world we live in can be represented, and what is our own position in it. Through processing the antiAtlas, we are trying to understand how people cross borders but also how borders modify their experience of space. New technologies of networked control settle spaces which are no more stretches but flows, loops, and interactions. These are virtual spaces, as the web spectacularly illustrates. The nation-state territory in its Westphalian meaning used to correspond to stretches, boundaries and marks. What is now humanly experienced, beyond this, is a daily life made of flows and networks. This addresses new questions to the way we conceive spaces, economically, culturally, and politically, and consequently our new experience of constructing social ties and communities. Communities are now provisional and shifting, they lay upon new alternatives and new forms of particpation, they do not encompass our whole lives any more. Such network forms imply a deep reconceptualization of the distinction between the public and the private sphere, the individual and the collective, the real and the virtual. To sum up, the main goal of this antiAtlas of borders is to understand the evolution of our political relation to space and to examine our common destiny.

Cédric Parizot – anthropologist, Institute for Research and Studies on the Arab and Muslim World (UMR 7310, Aix Marseille Université, CNRS) and the Institute of Advanced Studies of Aix Marseille University (IMéRA)

Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary – geographer, Laboratoire Pacte (UMR 5194), Université J. Fourier, Grenoble

Antoine Vion – sociologist, AMU, Laboratoire d’Économie et de Sociologie du Travail (UMR 7317 Aix Marseille Université, CNRS)

Gabriel Popescu – Geographer, Indiana University South Bend

Jean Cristofol – philosopher, École Supérieure d’Art d’Aix-en-Provence (ESAA)

Isabelle Arvers – Curator and producer

Nicola Mai – video performer, anthropologist, London Metropolitan University, Londres

Joana Moll – media artist

With the help of Ruben Hernandez-Leon for the English version

Aix en Provence, september 2013